Limited COVID-19 Testing? Researchers In Rwanda Have An Idea

Like many countries, Rwanda is finding it impossible to test each of its citizens for the coronavirus amid shortages of supplies. But researchers there have created an approach that’s drawing attention beyond the African continent.

June 12, 2019Like many countries, Rwanda is finding it impossible to test each of its citizens for the coronavirus amid shortages of supplies. But researchers there have created an approach that’s drawing attention beyond the African continent.

They are using an algorithm to refine the process of pooled testing, which tests batches of samples from groups of people and then tests each person individually only if a certain batch comes back positive for COVID-19. Pooled testing conserves scarce testing materials.

Rwanda’s mathematical approach, the researchers say, makes that process more efficient. That’s an advantage for developing countries with limited resources, where some people must wait several days for results. Longer waits mean a greater chance of unknowingly spreading the virus.

Those behind the algorithm have expressed some pride that a potential solution to a dogged problem in the global crisis is coming from Africa. Experts have noticed. Sema Sgaier, a Harvard assistant professor of global health, called the Rwanda approach an example of the “incredible solutions in very resource-poor settings” that have come out of the continent.

Some experts, and even the researchers, have noted concerns that the complexity of the approach could deter its widespread use. “If you told this to a technician, they would say, ‘What a mess. I want a simple scheme,’” Sigrun Smola, a molecular virologist at Saarland University Medical Center in Germany, told the journal Nature in a recent article on Rwanda’s and other approaches to pooled testing.

The method developed by Wilfred Ndifon, a mathematical epidemiologist and director of research at the African Institute for Mathematical Sciences Global Network in Rwanda’s capital, Kigali, is now being turned into software that will guide lab technicians, minimizing human error.

“The technician will continue to do the normal lab work,” Ndifon told The Associated Press. The software “will make it easier to make the calculations.” It will tell the lab tech how many samples to put together for testing and, in the end, how many samples are infected.

The approach is the most efficient in places where virus prevalence is relatively low, the researchers say.

“The algorithm itself is novel,” Ndifon said. It reduces the number of required retests when a group sample comes up positive. Rather than retest every sample in the batch individually, the mathematical formula dictates how to create and overlap smaller groups from the batch in a way that allows the positive samples to be identified.

He described it as arranging samples in a multi-dimensional structure such as a cube or hypercube and testing along the slices.

“In terms of visual representation, it’s quite beautiful,” he said.

The second novelty is speed. Each round of testing takes about three hours, Ndifon said, and this approach needs just two rounds.

The researchers have said they were able to pinpoint a positive sample in a pool of 100. They have found that the failure rate is .001%, “effectively zero,” Ndifon said.

Rwanda has one of the lowest confirmed virus caseloads in Africa with over 2,100 infections, and the World Health Organization has pointed to the country as one that has done well in responding to the pandemic. Rwandan authorities have credited citizens with cooperating with the government’s guidelines.

The East African nation has conducted more than 300,000 tests for the virus. Each test costs about $50, Ndifon said, but their approach saves more than half of that money.

“Using technology solutions has helped to reduce pressure on our health system,” said Sabin Nsanzimana, an epidemiologist on Rwanda’s task force fighting COVID-19.

Now other African countries including South Africa are interested in using the approach, the researchers say.

Leon Mutesa, a Rwandan professor of human genetics and a member of the government’s COVID-19 task force, is one of the experts supervising the implementation of the new approach.

He said it’s giving hope and confidence to Rwandan health workers who had watched with horror the images of the pandemic spreading in Europe.

“It’s quicker and saves money. So we have been able to test many people,” he said.

See Also:

Bribery, Lashes, Death And TVE...

Rehabilitation or transit centers are spread across different parts of Rwanda. As per official narra...

Articles

Why Kagame Would Not Win A Fre...

In a hypothetical scenario where free and fair elections were conducted in Rwanda, it is highly ques...

Commentary & Analysis

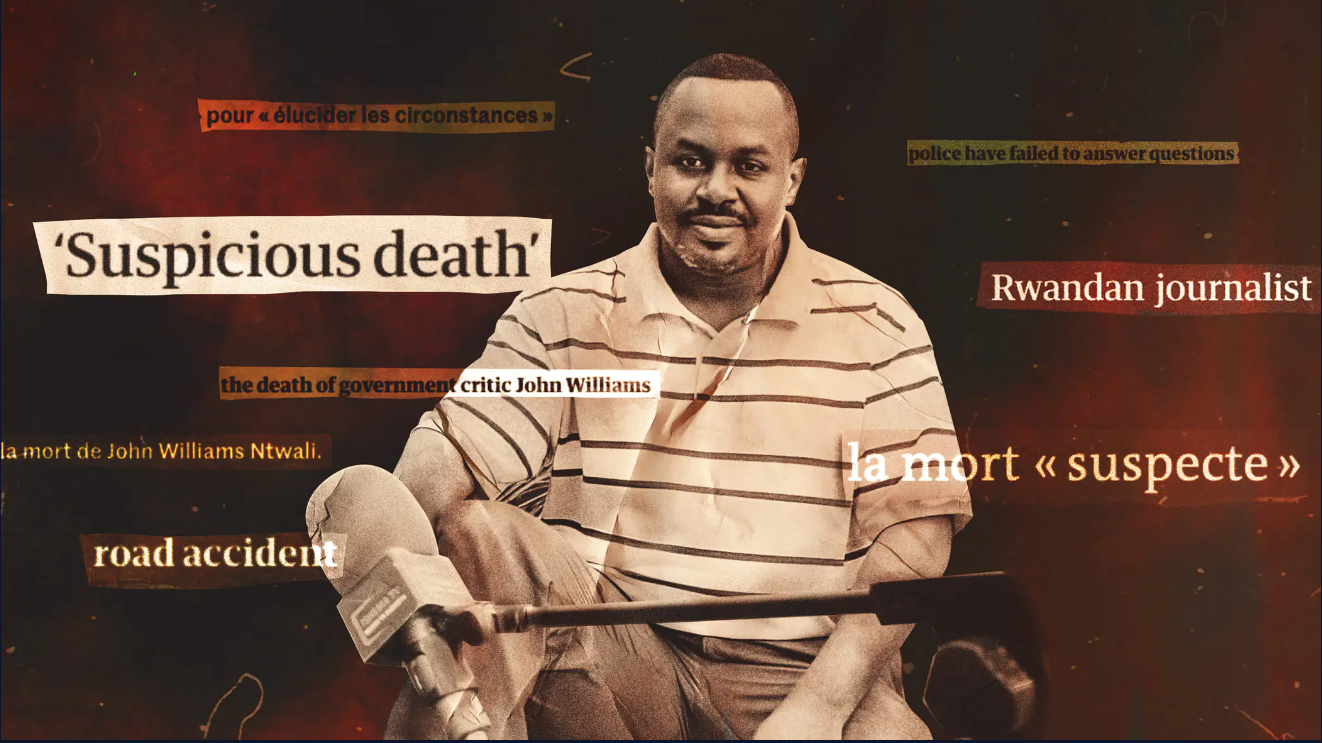

Denying A Genocide By Investig...

They are going to say that we deny the genocide,” the colleague at Forbidden Stories – the project o...

The Rwanda Classified Project Investigations

Kagame’s Dual Grip: Repression...

Paul Kagame's regime in Rwanda is a striking example of how modern autocrats keep a firm hold on pow...

Commentary & Analysis