Sex Workers Lack Food For Taking HIV Drugs During Covid-19

As the coronavirus spreads in Africa, it threatens in multiple ways those who earn their living on the streets — people like Mignonne, a 25-year-old sex worker with HIV.

October 6, 2021As the coronavirus spreads in Africa, it threatens in multiple ways those who earn their living on the streets — people like Mignonne, a 25-year-old sex worker with HIV.

The lockdown in Rwanda has kept many of her customers away, she said, so she has less money to buy food. And when she doesn’t eat, the antiviral drugs she takes for HIV can bring on pain, weakness and nausea, or even make her pass out.

“Yet it’s equally dangerous when you don’t take the drug,” Mignonne said in an interview. “You will die.”

Similar challenges exist elsewhere in Africa, which has the world’s highest burden of HIV.

Studies have shown that food insecurity is a barrier to taking the drugs daily and can decrease their efficacy, affecting not only sex workers but anyone where food — or the money to buy it — is scarce.

Among sex workers in Zimbabwe’s capital, Harare, “most who are living hand-to-mouth have been lamenting that it’s making it difficult to adhere to treatment,” said Talent Jumo, director of the Katswe Sistahood, an organization for sexual and reproductive health.

That’s a danger as many sex workers around the world are excluded from countries’ social protection programs during the COVID-19 pandemic, researchers from the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine and elsewhere wrote in a new commentary for The Lancet.

“Sex workers are among the most marginalized groups,” they wrote, adding that “it is crucial that disruption to health services does not further reduce access to HIV treatment.”

Rwanda, which offers free antiretroviral therapy to all, has been widely praised for its progress in controlling HIV. The country has kept HIV prevalence at 3% for more than a decade and the number of new infections has dropped.

But sex workers and health experts warn that those gains could be lost.

More than 45% of the estimated 12,000 sex workers in the East African country live with HIV. Not taking the antiretroviral therapy risks spreading the virus, said Aflodis Kagaba, a medical doctor and executive director of Health Development Initiative, a local organization that promotes better access to health care.

The organization has been giving some sex workers food, hand sanitizer and hygiene materials and is talking with the government about budgeting aid for sex workers.

“Sex workers are part of the society and they deserve to live a healthy life,” Kagaba said.

In Migina, an entertainment area in the capital, Kigali, Mignonne acts as a leader of 60 sex workers, reminding colleagues with HIV to take their antiretroviral therapy and visit health centers every month.

“Now many are telling me they cannot take the drug because they don’t have food. It’s understandable and I don’t know what to do,” she said. She, like other sex workers, gave only her first name for her safety.

Rwanda was distributing food to households under lockdown but stopped after three months. It has since lifted lockdown restrictions for some businesses, but others such as bars are still closed.

Now COVID-19 cases are rising more quickly, prompting authorities to impose a nighttime curfew. As of Saturday, the country had more than 1,000 confirmed coronavirus cases.

“We are seeing sex workers in Africa being denied the support others are given, like food,” UNAIDS chief Winnie Byanyima said this month. “Some are being shamed and run out of their homes and called the source of corona.” Her organization and the Global Network of Sex Work Projects have called for sex workers to be included in countries’ COVID-19 social protection programs.

UNAIDS is also warning about possible shortages of medication for millions of people with HIV in the next two months, especially in developing countries. Lockdowns and border closures are slowing the drugs’ production and distribution.

A World Health Organization survey of 99 countries found 32% already reporting disruptions to established antiretroviral therapy, Meg Doherty, director of the U.N. agency’s department of HIV, hepatitis and STIs, said this week.

“We are engaging in unsafer sex practices because we can’t be able to access prevention tools or to drugs that we are used to,” Grace Kamau, a Kenya-based coordinator with the African Sex Workers Alliance, told a COVID-19 global webinar for sex workers last month. A sex worker walks on a street in Harare, Zimbabwe (Tsvangirayi Mukwazhi)

Agnes, an HIV-positive sex worker in Kigali, said new stigma also hurts.

Before the coronavirus it was easy to make money, she said. Now “you cannot dare go on the streets, yet back in communities we are treated like outcasts,” the 26-year-old told The Associated Press. “During the lockdown, when local leaders distributed food, my family was skipped on account that I was a sex worker.”

Local officials have denied discriminating against sex workers.

Like many others, Agnes quickly consumed her small savings she had intended to use on running a business selling tomatoes. Now, like many others, she has no lifeline.

Deborah Mukasekuru, the coordinator of the National Association for Supporting People Living With HIV, called it a “difficult situation.”

“We try to mobilize food for sex workers, but they are many and we cannot feed all of them,” she said. “You cannot blame the government because corona caught the government unaware.”

___

Cara Anna in Johannesburg contributed.

See Also:

Bribery, Lashes, Death And TVE...

Rehabilitation or transit centers are spread across different parts of Rwanda. As per official narra...

Articles

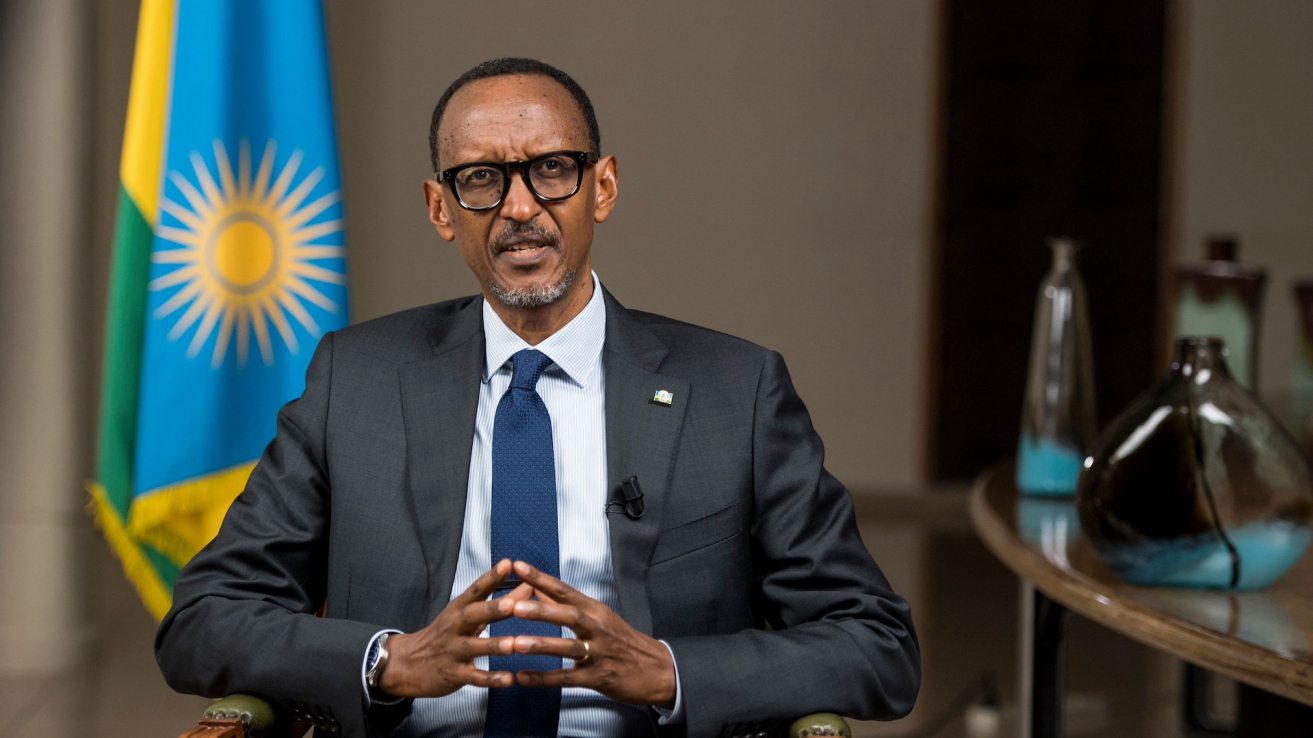

Why Kagame Would Not Win A Fre...

In a hypothetical scenario where free and fair elections were conducted in Rwanda, it is highly ques...

Commentary & Analysis

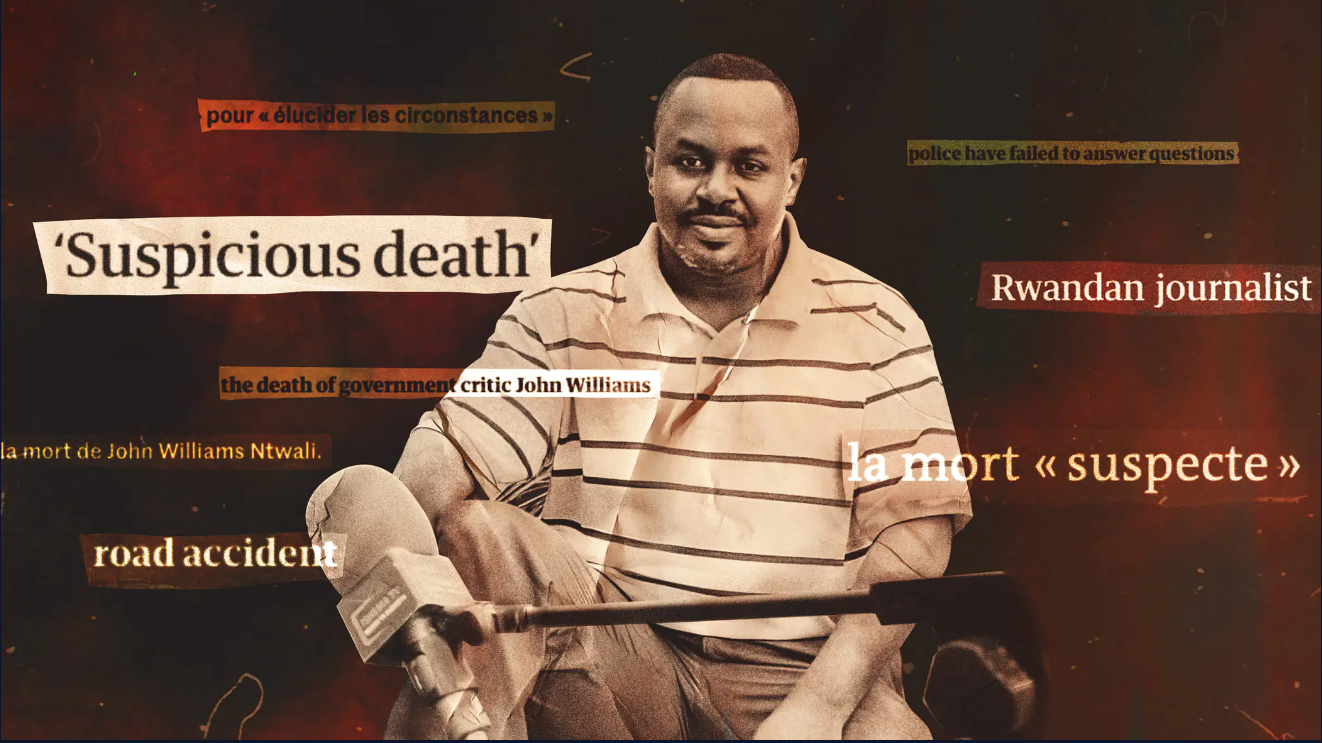

Denying A Genocide By Investig...

They are going to say that we deny the genocide,” the colleague at Forbidden Stories – the project o...

The Rwanda Classified Project Investigations

Kagame’s Dual Grip: Repression...

Paul Kagame's regime in Rwanda is a striking example of how modern autocrats keep a firm hold on pow...

Commentary & Analysis