Jourmalists cover a story at Rwanda Investigation Bureau heaquarters in Kigali on May 17, 2019. Photo: File. Newtimes Rwanda

In the early months of 2024, my book “From watchdogs to Traitors” will be published and it will discuss every conner on how the media in Rwanda operates through my own experience mainly telling the story and exposing the assault on one of the journalism’s fundamental principles of telling the truth. As you are patiently waiting to move with me through and with me in these pages, I decided in this article to discuss with you the evolution of Journalism in my country Rwanda.

In 2021 I submitted two petitions to the Supreme Court of Rwanda regarding certain articles in the penal code that I believe restrict press freedom and freedom of speech. Some of these petitions yielded positive outcomes, while others did not. While numerous positive stories and glamorous statistics about Rwanda are widely known and readily available, there is another side to the narrative. That side should not be undermined because if thoroughly explored it may present irrefutable realities that the available narrative.

From my perspective and experiences, the media landscape in Rwanda is distinct and complex compared to many other countries in the same bracket. The complexity of media practice in Rwanda has led to the imprisonment of many professional Journalists while others disappeared without a trace. I don’t want to tell you that among a few road accidents that take lives in Rwanda, journalists are very unlucky that they have a number.

The challenges are easily evident as some wounds from the past are still fresh for the victims, authorities use the situation to shift goal posts in media practice, making the professional individuals remain learners of the ever-changing situation. These challenges compound the existing legal obstacles to press freedom, speech, and expression. Consequently, self-censorship prevails, as individuals fear both public conflicts and the repercussions of crossing the red lines set by the government authorities.

The Catholic Church in Rwanda in 1933 published the country’s first-ever newspaper, marking the birth of journalism in Rwanda. These newspapers served the nation for over three decades until the 1960’s when the Hutu-led extremist government established its own radio station and print newspaper. These new media outlets coexisted with the existing Catholic publications until the 1990s when Rwanda witnessed a proliferation of media platforms. However, throughout this period of growth, the importance of press freedom ideals was not established.

During that time, journalists lacked adequate training and education in journalistic principles, law and ethics and there was locally a lack of a code of conduct for their practice. Nepotism played a significant role in hiring, favouring individuals with connections in the government.

For the Roman Catholic Church, one just had to be a staunch believer in the church doctrines and the ambitions to enforce “Jesus and his mother’s kingdom” in Rwanda that qualified one to be a journalist in their media outlets. Between 1990 and 1994, the government orchestrated the genocide and exploited the media as a tool. This narrative underscores the harmful impact of censorship and propaganda on society.

In Rwanda, we are often told that excessive freedom of speech led the media to mobilize and promote hate speech. However, my viewpoint, informed by experience and extensive background study in Rwanda, diverges from this interpretation. In reality, it was not an issue of excessive freedom but rather a systematic propagation of media, sponsored by the government, aimed at spreading propaganda and hate speech. This ultimately resulted in a genocide that claimed the lives of over a million Tutsi, including my relatives.

From this perspective, media freedom and its detachment from the state saves the society while the vice versa deems the society to danger. Unfortunately, the Kigali government is ignoring this fact and fellow journalists seek recognition from authorities just like the media before the Genocide.

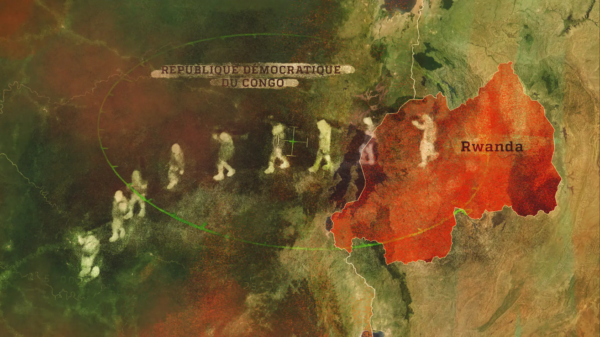

During the period leading up to the genocide in Rwanda, there was a fierce conflict between the government military and the Rwanda Patriotic Army (RPA) who were rebels by then. The government and military utilized national radio and other private media platforms to disseminate a dangerous “kill or be killed” narrative, which further escalated the violence.

My country has failed to learn from this tragic history, individual and government continue to pedal the same political behaviour. Unfortunately, the government blames the media for the propaganda that was beleaguered by the government. The media is too weak to refute back – to negate that label and rather point to the government’s graver mistakes of limiting press freedom and enforced collaboration.

Through a systematic propaganda campaign, the pre-genocide government and various media outlets referred to Tutsis in derogatory terms such as “cockroaches,” revealed their hiding places, and urged Hutus to slaughter their Tutsi neighbours. Journalists played a significant role in inciting violence through their broadcasts, and many of them – on individual basis faced justice after the 1994 genocide against the Tutsi population.

Radio Muhabura, established by the Rwanda Patriotic Front in 1991 during the war, operated from Uganda and eventually reached all Rwandans, except those in the southern region who began tuning in by 1992. Radio Muhabura served as a means to promote RPF ideas to Rwandans back home.

In January 1993, RTLM (Radio-Television Libre des Mille Collines), translated as “The Independent Radio and Television of a Thousand Hills,” went on air. Both radio stations accused each other of wrongdoing. Radio Muhabura accused the Rwandan government of committing genocide and consistently denied RPF involvement in civilian killings through its daily broadcasts.

It’s one of the significant situations in Rwanda where the media was politicised, fully biased on political ambitions of groups. In simple terms the media died and politics-built towers on its graveyard.

Although the pro-Hutu radio station, RTLM had a larger audience, particularly in Rwanda, Radio Muhabura had its specific audience due to its broadcasts being primarily in English. The existence of Radio Muhabura was cited as part of the defence during the trial of Ferdinand Nahimana, the co-founder of RTLM, at the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda.

Initially, RTLM heavily criticized the peace talks between the RPF and President Juvenal Habyarimana, who, along with his family, provided substantial support to the station. You can already see that the media was busy dancing the tunes of ethnic ideologies the politicians crafted for their own benefits.

RTLM quickly became well-known for its approach and easily captured the hearts of the youth, who later transformed into the Interahamwe militia who later killed the Tutsi. The station received significant assistance and backing from Kangura Magazine which will be discussed more in the pages of my book.

Felicien Kabuga one of the richest Rwandans at the time allegedly provided extensive support in the management and financing of RTLM and Kangura. RTLM conducted propaganda for the government and defended the Hutu Power ethnic ideology. This exemplifies the extent to which propaganda permeated the Rwandan media landscape.The influence of RTLM extended beyond the radio waves. Kangura Magazine, a publication known for its virulent anti-Tutsi content, often complemented the station’s programming.

The power of media in shaping public opinion and fuelling violence became evident during the genocide. The dissemination of hate speech and propaganda through radio and print media contributed to the dehumanization and subsequent mass killings of the Tutsi population. The media’s role in amplifying division and promoting violence highlights the importance of responsible journalism and the need to guard against the manipulation of information for destructive purposes.

It is important to reflect on these events and learn from them, recognizing the devastating consequences of media manipulation and hate speech. The Genocide in Rwanda stands as a grim reminder of the dangers posed by unchecked propaganda and the vital role media plays in promoting tolerance, understanding, and peace.

RTLM received support from Radio Rwanda, which was under government control and utilized its equipment for broadcasting. Not only did this radio station spread hate propaganda against Tutsis, but it also targeted moderate Hutus, Belgians, and the United Nations Mission assistant to Rwanda, UNAMIR.

After the genocide, from the end of 1994 to 2003, Rwanda underwent a transition period. The transition period was defined by the Arusha Accord and concluded with a referendum on the 2003 constitution, as well as presidential and parliamentary elections. The Rwanda Patriotic Front (RPF) has remained in power since then, and there are striking similarities between the media landscape before and after the 1994 genocide against the Tutsi population.

In general, the Rwanda Patriotic Front is intolerant to criticism or challenges to its authority. Journalists have faced forced exile, violence, disappearance, and arrests Including myself. Through my eyes, I experienced the sensitive nature of certain topics that are not allowed to be reported about. Post-genocide media restrictions have been a part of my lived experience and my book “From Watchdogs to Traitors” speaks more about it.

Since 2000, there has been strict control over the media and its output. Laws have been enacted, such as media laws, and other legislation within the penal code and other legal frameworks, which serve to create a censorship environment in newsrooms. The structure of these laws in Rwanda, particularly concerning press freedom and freedom of expression, often contradict one another and are intended to stifle critical reporting. Differentiating between “country or national interest” and “government interest” is one of the major challenges within the Rwandan community and even in the newsrooms.

The media landscape in Rwanda in 2023 is complex, and to gain a better understanding, one should refer to the 2022 World Press Freedom Index by Reporters without Borders (RSF), which ranks Rwanda 136th out of 180 countries. According to RSF, this low ranking is a result of journalist intimidations, arrests, kidnappings, killings, self-censorship, and the perception of the public. Many of the stories shared in my book revolve around these issues as witnessed through my own eyes.

The Rwanda Governance Board (RGB) serves as the official media governing body in Rwanda. It frequently refutes reports from various organizations, including the Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ), RSF among others and paints a picture of great progress, often pointing to the increase in media outlets. Nevertheless, the political environment plays a crucial role in determining the strength of press freedom and freedom of expression. In Rwanda, the political system leans toward a consensual and mutual understanding among political actors, which restricts open discussions or engagement on certain topics.

Reporting on anything perceived, as wrongdoing by the government or its affiliated institutions and individuals, as well as sensitive societal issues, is enough to label someone an enemy of the state and unpatriotic. The repercussions can extend beyond the online space and many journalists have paid a heavy cost.

Within the pages of “From Watchdogs to Traitors” you will embark on a gripping journey, uncovering the intricate tapestry of Rwanda’s media world. Ultimately, it is a testament to the enduring quest for truth in the face of adversity and the unwavering commitment to upholding the principles of journalism.