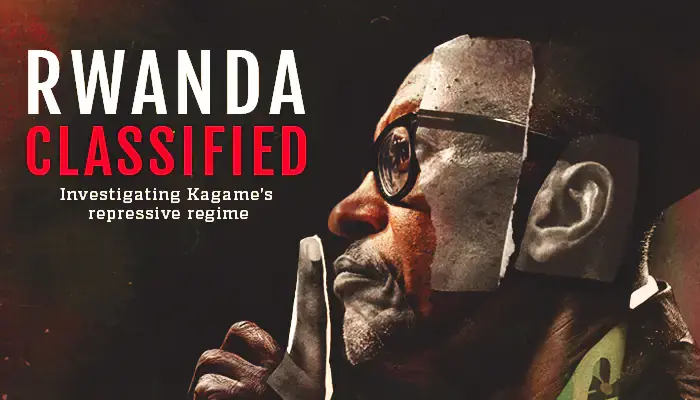

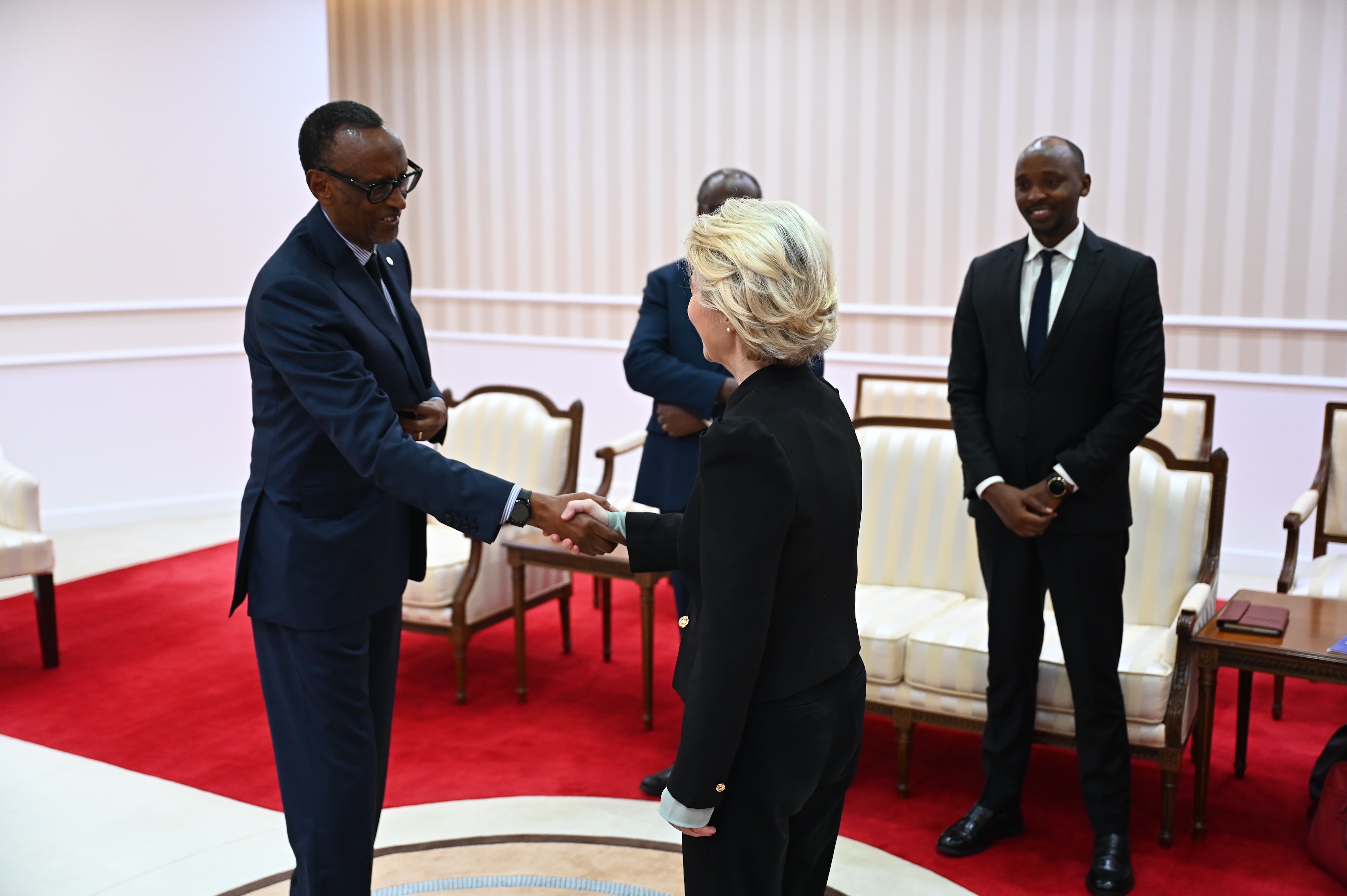

European Commission president Ursula von der Leyen is just one in a long line of EU leaders who’ve embraced Rwandan president Paul Kagame.

She last did so amid EU overtures to accessRwanda’s minerals, knowing full well he stood credibly accused of war crimes, assassinations, and torture in Africa.

But did she know he is also terrorising Rwandan dissidents much closer to home — on the streets of Brussels?

Fear of being poisoned by Kagame’s agents is widespread in the Rwandan diaspora in Belgium.

Even high-profile African activists, such as Paul Rusesabagina and Denis Mukwege, aren’t safe when they visit the home of the EU institutions.

Some Rwanda-associated poisons can be administered via a handshake or soaked into an item of clothing.

The last time von der Leyen shook Kagame’s hand was on 18 December 2023 on a visit to Kigali.

“Unfortunately … she did not have a chance to enjoy the local cuisine. However, she did have the chance to try Rwanda’s excellent coffee,” her spokesperson said.

No one is seriously suggesting the Rwandan leader would dare to poison a high-level EU politician.

But even though EU leaders themselves are physically safe, they still ought to worry about their moral hygiene — because every time they meet Kagame, they embolden him to commit further crimes by giving him a sense of impunity.

And that means their handshakes are putting Rwandan dissidents who live in Europe, as well as in Africa, in clear and present danger.

Paul Kagame with Ursula von der Leyen in Kigali in December 2023 (Source: European Commission)

Toxic handshake

Rusesabagina is the real-life hero of the 2004 film Hotel Rwanda about the 1994 genocide, who is hated by Kagame and who now lives in the US.

And when Rusesabagina came to Brussels for a family wedding in August 2024, he was urged to take special care by his Belgian and US security advisers, who spoke to EUobserver.

They warned him not to travel or stay anywhere alone, not to use unfamiliar taxi drivers, not to meet strangers or accept gifts from them, not to use his normal mobile phone, and not to hire a car.

Part of their advice was designed to evade Rwandan electronic surveillance, since Kagame’s agents had already once kidnapped Rusesabagina, in Dubai in 2020.

But another part was because Kagame has a track record of transnational assassinations, including by poison.

“The Rwandans are master poisoners. There’s one toxin that can be administered via a handshake: The assassin smears it onto the palm of their hand, shakes the victim’s hand on some pretext, then walks away and takes an antidote to save themselves,” said a Belgian security source, who asked not to be named.

Rusesabagina’s adopted daughter, Carine Kanimba, told EUobserver: “My family was really worried about my father coming to Belgium because it’s like a playground for them [Kagame’s intelligence service]. This is where they have full access. They can hurt you. They’ve killed people here before”.

Kanimba was orphaned in the genocide while she was an infant and is now a human-rights activist living in the UK.

The family marriage in Brussels (her cousin’s) was followed by Kanimba’s own wedding, near Verona in Italy, also in August.

While planning the two events, the family notified Belgian and Italian intelligence services, hired private security guards, and vetted catering staff and equipment to make sure their food was safe.

“My wedding was meant to be full of love, and it was, but everyone in the family was conscious of the risk,” Kanimba said.

“It might sound like a movie, but it’s not — there have been a lot of people who dropped dead because of poisoning by the regime,” she said.

Kanimba herself has faced death threats, issued in person to relatives and on social media.

“One of Kagame’s top aides said on X that I deserved a ‘golden machete’, which shocked me to the core, because my parents were probably killed with a machete [in the genocide],” she said.

Kanimba’s phone was also hacked with Israeli-made Pegasus spyware in 2021, which is sold to states’ intelligence services.

“I’ve learned over the years, the more that we talk publicly about such threats, the safer we become,” she said.

“But the the fact I’m having this conversation with you today, so many people have been killed for the kind of conversation we’re having [about Kagame],” Kanimba said.

Carine Kanimba (r) receiving a human-rights award in London in November 2023 (Source: Magnitsky Awards)

For his part, Mukwege is a Congolese gynaecologist who won the Nobel Peace Prize in 2018 for helping rape victims and who has spoken out against use of rape by Rwandan soldiers and Rwanda-linked rebel groups in Africa.

Mukwege also won the European Parliament’s Sakharov award in 2014.

But when he came to Brussels on a trip in May 2015, he was put underclose surveillance by Rwanda’s embassy.

Mukwege had received a courtesy car from the EU parliament, but when he arrived at the offices of Belgian newspaper Le Soir for a welcome reception, journalists recognised his driver as being a member of the Rwandan embassy’s security staff and advised Mukwege to insist on a different chauffeur.

Mukwege told Belgian friends at the time how the bogus driver, who had infiltrated the parliament’s car-pool, had behaved on the way.

He had begged Mukwege to hold his mobile phone and speak to his friends because he was so famous, which Mukwege refused to do.

Mukwege, who is based in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), declined to speak with EUobserver.

But the same bogus driver also offered him a suspicious tie on the same pretext, according to a contact in his Panzi Foundation in DRC.

And, according to two Belgian security sources who asked not to be named, the tie, which Mukwege also declined to touch, had been laced with poison.

Recalling how it happened, one of the Belgian sources told EUobserver: “He [Mukwege] got into a car with a driver who he didn’t know, and the guy said to him: ‘Dr Mukwege, you’re my hero! Please accept this tie as a humble gift. It would make me and my family so proud if you were to put it on’.”

‘Munyuza’s droplets’

Less well-known people are all the more vulnerable.

Rwanda was a Belgian colony until 1962 and Belgium is home to some 20,000 to 30,000 people of Rwandan origin – its largest diaspora community in the world.

Most of them live scattered in small towns in the Flanders region, such as Aalst or Dendermonde.

Those of them who are genocide refugees still feel traumatised and divided.

But Rwandans also come together at church and music events, with 2,000 to 3,000 guests expected to visit the Inyange folk-dance festival in Brussels on 23 November, for instance.

One of those taking part in the festival, Rwandan human-rights activist Natacha Abingeneye, who lives in Aalst, believes Kagame’s agents murdered her father in Brussels in 2005.

He was a former government minister in Rwanda, was giving evidence to the UN’s International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda when he went missing, and his mutilated body was later found in a canal in the EU capital.

Abingeneye herself became a target when her civil society group, Jambo, tried to organise a debate on Rwanda in the Belgian parliament in 2018.

Her name was smeared in dozens of articles in Kagame-linked media, claiming, for instance, that she had funded Rwandan death squads in 1993, even though she would have been seven years old at the time.

“There was also suspicious behaviour at my home, but not enough to press charges [with Belgian police],” she told EUobserver.

“Sometimes, I’d see a car had been following me all the way from Brussels to the roundabout near where I live, and I’d just continue driving because I was scared to stop, as I was alone,” she said.

“Shady figures would come to my door, ring the bell, and run away,” she added.

Denis Mukwege at the European Parliament in Brussels in 2016 (Source: European Parliament)

Speaking of the fear caused specifically by regime poisoners, she said: “It’s not mythology. It’s reality. It’s a method that they have used so much in Rwanda that it even has a name in Rwandese: ‘utuzi twa Munyuza’, which means ‘droplets of Munyuza’s waters’.”

The phrase refers to Dan Munyuza, who is now Kagame’s ambassador to Egypt, and who was exposed in a conversation leaked on Youtube to have plotted poisonings of Rwandan dissidents abroad.

“Everyone knows that if they want to eliminate you, we share a coffee, you go home, I go home, I’m dead, and no one knows what happened,” Abingeneye told EUobserver.

“The other day, I went to a team-building event in a bar. I left my drink, went away, picked it up again and everybody was like: ‘Are you crazy?’,” she said.

“It [poisoning] is as quick as a wave of someone’s hand over your glass,” she added.

Her father’s 2005 death is not the only one which has caused suspicion in the Rwandan community.

Rodolphe Shimwe Twagiramungu, for example, was a 34-year-old Rwandan musician who went to a nightclub on Avenue Louise in Brussels on 17 April 2022 and who was found dead in a nearby street the next morning from unknown causes.

Twagiramungu’s father had been a former Rwandan prime minister and another Kagame enemy.

And the Rwandan diaspora aside, if you are a white Western national it doesn’t necessarily mean you are untouchable.

Urban legend

Many Congolese people in Belgium even believe Kagame once poisoned the then-Belgian foreign minister, Louis Michel, in 2002.

Michel visited Kigali while calling out Kagame for fuelling conflict in DRC, but fell gravely sick when he returned to Europe and collapsed at a Nato summit in Reykjavík.

Michel, who is the father of outgoing EU Council president Charles Michel, didn’t reply to EUobserver.

But one Belgian contact who knew him said: “After this incident, one thing is sure: Louis Michel never criticised Rwanda again”.

The Michel-poison theory is seen as an urban legend by Belgian security services because the potential cost of a major diplomatic incident if it got out far exceeded the benefit of silencing him.

“Kagame may be dangerous, but he’s not stupid, and he would do a cost/benefit analysis on every case. It’s much more likely Michel was infected by a bacteria or virus, which happens easily enough in Africa,” a Belgian security source said.

But when Canadian writer Judi Rever, who wrote a Kagame-critical book, visited Belgium in 2014, Belgium gave her two bodyguards after receiving intelligence the Rwandan embassy in Brussels planned to hurt her.

Natacha Abingeneye in Aalst, Belgium, in October 2024

Some Belgian journalists living in Brussels who spoke to EUobserver asked not to be quoted in this article because of personal security fears.

And Peter Verlinden, a former journalist and now politician living near the Belgian town of Leuven, who wrote a Kagame-critical book in 2015, still requires special protection nine years later.

“To this day, my wife and I are under a specific protection system by Belgian security services. I can’t reveal how it works, but if we ever needed help, we can just call and a rapid response [police] unit arrives in minutes wherever we might be,” he told EUobserver.

Verlinden has received death threats on his phone and on social media and, as with Kanimbe, Belgian intelligence services found Pegasus on his mobile.

“I think the aim of the [Rwandan] regime in Europe is to cause fear, not to kill,” Verlinden said.

“But if I go to an event with Africans, I only eat from the public buffet and I always serve my own plate [for fear of poison]. I wouldn’t use a Rwandan taxi driver whom I didn’t know,” he said.

Designer drugs

The use of sophisticated poisons in targeted assassinations in Europe is more readily associated with Russia.

But even if Rwanda’s spy services were tiny compared to Russia’s, that didn’t mean it couldn’t acquire frightening capabilities if it wanted to, said Belgian forensic toxicologist Jan Tytgat.

“Novichok is absolutely available on the dark web and we should be concerned about its potential use around the world,” he said, referring to a Russian-made nerve toxin.

“There are pages where you can ask AI: ‘Please design me the newest generation of organophosphates to kill people’ – it’s crazy,” he added.

Tytgat has worked with Belgian police on more run-of-the-mill cases.

He is also professor of pharmacology at KU Leuven university in Belgium and has done research into new medicines in the field in Africa.

A handshake poison could be made from ‘designer drugs’, such as fentanyl derivatives, he said.

“People have designed synthetic molecules that are 10,000 times more potent than morphine. You put a few crystals in the palm of your hand, and if you give a strong handshake, a couple of those crystals will humidify on the sweat and skin of your victim, and this is really sufficient to put them in a comatose state,” Tytgat said.

The assassin could protect themselves by taking an antidote, putting ointment on their hand, or wearing gloves.

A necktie poison could be made from African plant extracts, as well as Novichok-type synthetic compounds, the Belgian toxicologist said.

It requires plants that are rich in atropine, but these are commonplace in central Africa.

Symptoms of atropine poisoning were “hallucinations, disturbed breathing, you have incredible thirst, you feel as dry as a bone, then you have neurological problems from which you can die,” Tytgat said.

He was not aware of any exotic poisoning cases in Belgium.

And in red-flagged incidents, Belgian authorities had access to equipment that could decipher a poisoner’s hidden signature, he said.

“With high-resolution mass spectrometers we can do isotope mapping [of poison molecules], and knowing the isotope load in a molecule you can, with some luck and some help from AI, devise where it was made and when it was made,” he told EUobserver.

But in day-to-day medical practice, atropine-type poisoning by an obscure Rwandan plant extract could be overlooked, he said.

“If you go to a full forensic toxicologist, initially we might also get a negative result, but we’d continue,” Tytgat said.

“In a standard hospital, I fear they might overlook uncommon plant- or animal venom-based intoxications, because of the protocols they follow in Belgium or in any other typical EU country,” he said.

Belgian toxicologist Jan Tytgat (Source: Jan Tytgat)

Another poison more native to central Africa is black mamba venom.

It can kill people in “five minutes,” Tytgat said.

But snake-venom proteins were too large to enter through a victim’s skin pores and would have to be injected, for instance with an insulin needle, which would be obvious to “any good pathologist,” he said.

Intervention Team

Rwanda’s embassy to Belgium is located in the green Woluwe Saint Pierre district in Brussels, some 15 minutes down the road from von der Leyen’s HQ.

When EUobserver took a photo of the building on 22 October for this article, a Rwandan man in a bright blue shirt jogged over to ask questions and surreptitiously filmed the reporter on his phone.

The Belgian foreign ministry declined to confirm how many Rwandan diplomats the embassy contained.

Belgian sources estimated it has some seven to 15 diplomats, as well as locally hired staff.

“About half of them [Rwandan diplomats] are probably intelligence officers under diplomatic cover, which would be a lot, by any normal standards”, a Belgian contact said.

The Rwandan embassy told EUobserver in an emailed statement: “Rwanda has a handful of diplomats accredited to the embassy and … their identities and roles are known to Belgian authorities”.

One of them is first secretary ">Gustave Ntwaramuheto, who was also accredited at the EU institutions until 2023, and who is a former military captain.

Ntwaramuheto declined to speak to EUobserver.

But, according to an investigation by Jambo in 2019, he is in charge of a task-force which carries out surveillance and violence against Kagame’s adversaries in Belgium.

“There are groups of thugs linked to the embassy. They call it the‘Intervention Team’ and they are highly organised. It’s professional, with a direct, national-level chain of command,” Jambo’s Abingeneye said.

Rwandan intelligence also spies on people’s comings and goings at Belgium’s Zaventem airport, according to Jambo.

Rwanda told EUobserver: “The Rwandan embassy in Belgium operates in accordance with international diplomatic standards and within Belgian law. Allegations made by politically-motivated actors [Jambo] known for their conspiracy theories … have no basis in fact”.

But the actions of Belgian authorities suggest otherwise.

Belgian intelligence services took the Rusesabagina family-wedding threat in August 2024 “seriously”, Kanimba said.

Rwanda’s embassy in Brussels (Source: EUobserver)

Persona non grata

And Belgium took an unprecedented step in April 2024 when it made Kagame’s new ambassador to Brussels, Vincent Karega, persona non grata before he even arrived, by declining his accreditation.

Karega had previously been expelled from DRC for backing rebels and had represented Kagame in South Africa in 2014, when a Rwandan exile was murdered there.

“No new [ambassador] candidate has been proposed by the Rwandan authorities,” the Belgian foreign ministry told EUobserver on 25 October.

Verlinden, the Belgian politician, said: “What has been lacking in Belgium until now has been political courage, but with the Karega decision, this seems to be a first sign that things are improving”.

But at the same time, Belgium’s capabilities are limited.

Its VSSE homeland intelligence service has slashed its Africa section over the past 10 years, recalling Kanimba’s fear that Belgium was Kagame’s “playground”.

The VSSE’s Africa department used to have some 25 posts in its heyday, but now had just one full-time and one part-time intelligence officer covering African threats, a Belgian contact said.

The VSSE declined to comment.

Normal bilateral relations despite the Karega row also mean that Belgian judicial authorities still cooperate with Kigali.

Belgian prosecutors raided Rusesabagina’s home in the Kraainem district in Brussels in 2020 and gave his private documents to Rwanda in the run-up to his Dubai kidnapping on the basis of a Rwandan extradition request.

“The 2020 search request was channelled officially by diplomatic means” and “carried out in strict compliance with Belgian law,” the Belgian Federal Prosecutor’s office told EUobserver on 20 October.

“We do not disclose figures, but judicial cooperation between Belgium and Rwanda [still] occurs regularly,” they said.

They added, however: “If the extradition request has a political character, [this] is a ground for refusal”.

“To date, no extradition has been accepted,” they said.

Ursula von der Leyen with Paul Kagame in Kigali last year (Source: European Commission)

EU whitewashing

Rwanda is rich in tin, tantalum, tungsten, and gold and signed a memorandum of understanding (MoU) with the EU on its mining sector in February.

The minerals deal would help “fight against illegal trafficking of minerals and … conflict minerals”, the EU commission told EUobserver, while opening up Rwanda to EU mining firms.

EU leaders at their summit in Brussels on 16 October also called for the creation of overseas return hubs for rejected asylum seekers.

But when asked by EUobserver if this might involve Rwanda, the commission said it “does not speculate on hypothetical scenarios”.

France relies on Rwandan troops to help protect French energy firms in nearby Mozambique from an Islamist insurgency.

French president Emmanuel Macron also gave Kagame and his wife a welcoming hug at a summit in France on 4 October.

And to add insult to injury for dissidents, Rwanda will host the UCI Road World Championships cycling race in September next year.

The international embrace of Kagame comes despite storied warnings that this emboldens him to do further violence.

EU parliament resolutions, reports by British civil society group Global Witness, and investigations by US group Human Rights Watch (HRW) have been ringing the alarm bell for years.

Reacting to the latest HRW report, the EU commission said: “We call on Rwanda to conduct prompt, impartial, and effective investigations into all allegations of torture … Perpetrators of any such acts should be brought to justice”.

Meanwhile, von der Leyen herself has lived in Belgium for over five years, amid regular Belgian media reports on Kagame’s harassment of Rwandans who also live there.

And the Belgian foreign ministry told EUobserver the “timing of the signing of this agreement [the EU’s minerals MoU] was unfortunate”, given Kagame’s behaviour.

“You can’t say you didn’t know – today there’s enough proof and documentation,” said Abingeneye.

Speaking of the cycling championship, Kanimba said: “Rwanda is beautiful, the hills are gorgeous, so I understand the cyclist community viewing my country as a good place for this, but it’s covering a lot of darkness and pain, it’s hurting our people”.

“It’s sportswashing at its core,” she added.

But top EU politicians who meet with Kagame do even more damage, activists say.

“They’re going on like it’s business as usual with a known murderer”, Kanimba said.

Abingeneye said: “If a European president stands in front of their people and shakes the hands of a killer, then they’re whitewashing his actions and they become partly liable for them”.

It made Kagame feel free to keep on hurting people “because you showed him there are no consequences”, Abingeneye added.

“I am Rwandan and European. I feel deeply European, but I’m so disappointed when I see this,” she said.

Emmanuel Macron with Kagame at the Élysée palace in Paris on 4 October (Source: Élysée)

This story was amended to correct the spelling of Paul Rusesabagina’s name and the date of his kidnapping in Dubai