Khadija Ismayilova’s home in Baku had become like a prison. In Azerbaijan, an oil-rich nation nestled next to the Caspian Sea that since 2014 has increasingly stifled free speech and dissent, Ismayilova’s investigations into the ruling family had made her a prime target of her own government.

The Azerbaijani investigative journalist knew she was constantly being watched – and had been told as much by friends and family who had been asked to spy on her.

The authorities had thrown the book at her: surreptitiously installing cameras in her home to film her during sex; arresting her and accusing her of driving a colleague to suicide; and eventually charging her with tax fraud and sentencing her to seven years in prison.

She was released on bail after 18 months and banned from leaving the country for five years.

So in May 2021, at the end of the travel ban, when Ismayilova packed away her belongings and boarded a plane to Ankara, Turkey, she may have thought she was leaving all of that behind.

Little did she know the most invasive spy was coming with her.

For nearly three years, Khadija Ismayilova’s phone was regularly infected with Pegasus, a highly-sophisticated spyware tool developed by Israeli company NSO Group that gives clients access to the entirety of a phone’s contents and can even remotely access the camera and microphone, according to a forensic analysis by Amnesty International’s Security Lab, in partnership with Forbidden Stories.

“All night I’ve been thinking about what did I do with my phone,” she told journalists from her temporary home in Ankara the day after learning her phone had been compromised. “I feel guilty for the messages I’ve sent. I feel guilty for the sources who sent me [information] thinking that some encrypted messaging ways are secure and they didn’t know that my phone is infected.”

“My family members are also victimized,” she added. “The sources are victimized, people I’ve been working with, people who told me their private secrets are victimized.”

Khadija Ismayilova (on left), with Pegasus Project journalist Miranda Patrucic from the OCCRP, when she learned her phone was regularly infected with Pegasus for nearly three years PBS/FORBIDDEN FILMS

The Pegasus Project

Ismayilova is one of nearly 200 journalists around the world whose phones have been selected as targets by NSO clients, according to the Pegasus Project, an investigation released today by a global consortium of more than 80 journalists from 17 media outlets in 10 countries, coordinated by Forbidden Stories with the technical support of Amnesty International’s Security Lab.

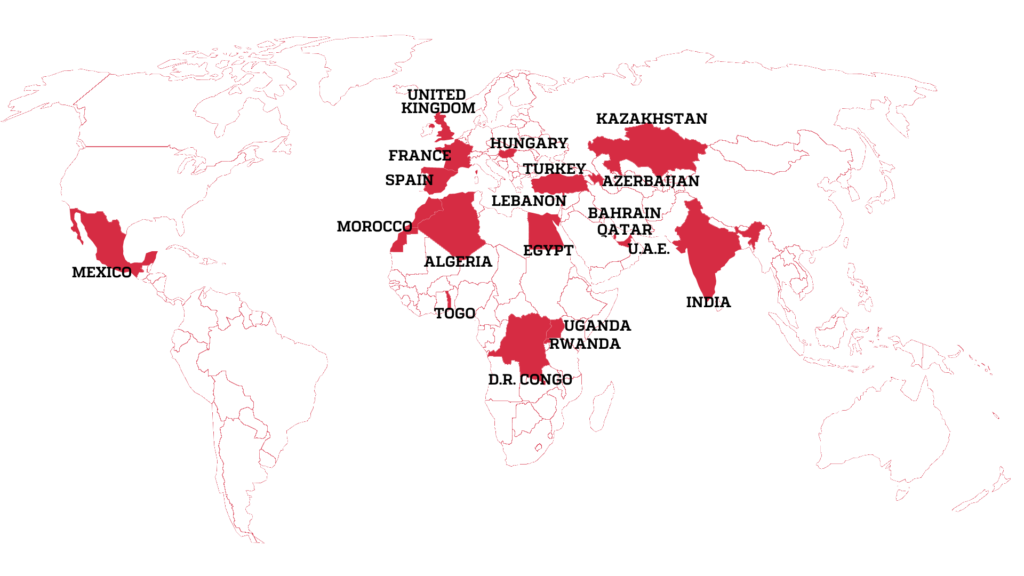

Forbidden Stories and Amnesty International had access to a leak of more than 50,000 records of phone numbers that NSO clients selected for surveillance. According to an analysis of these records by Forbidden Stories and its partners, the phones of at least 180 journalists were selected in 20 countries by at least 10 NSO clients. These government clients range from autocratic (Bahrain, Morocco and Saudi Arabia) to democratic (India and Mexico) and span the entire world, from Hungary and Azerbaijan in Europe to Togo and Rwanda in Africa. As the Pegasus Project will show, many of them have not been afraid to select journalists, human rights defenders, political opponents, businesspeople and even heads of state as targets of this invasive technology.

Stating “contractual and national security considerations” NSO Group wrote in a letter to Forbidden Stories and its media partners that it “cannot confirm or deny the identity of our government customers.” Forbidden Stories and its media partners reached out to each of the government clients cited in this project, all of whom either failed to respond to the questions by the deadline or denied being clients of NSO Group.

It is impossible to know whether a specific phone number appearing in the list was successfully compromised without analyzing the device. However, Amnesty International’s Security Lab, in partnership with Forbidden Stories, was able to perform forensics analyses on the phones of more than a dozen of these journalists – and 67 phones in total – revealing successful infections through a security flaw in iPhones as recently as this month.

The leaked phone numbers, which Forbidden Stories and its partners analyzed over months, reveal for the first time the staggering scale of surveillance of journalists and human rights defenders – despite NSO Group’s repeated claims that its tools are exclusively used for targeting serious criminals and terrorists – and confirm the fears of press advocates about the scope of spyware being used against journalists.

“The numbers vividly show the abuse is widespread, placing journalists’ lives, those of their families and associates in danger, undermining freedom of the press and shutting down critical media,” said Agnes Callamard, secretary general of Amnesty International. “It is about controlling public narrative, resisting scrutiny, suppressing any dissenting voice.”

Journalists appearing in these records have received legal threats, others have been arrested and defamed, and some have had to flee their countries due to persecution – only to later find that they were still under surveillance. In rare cases journalists have been killed after having been selected as targets. Today’s revelations make clear that the technology has emerged as a key tool in the hands of repressive government actors and the intelligence agencies that work for them.

“Putting surveillance on a journalist has a very strong chilling effect,” Carlos Martinez de la Serna, program director at the Committee to Protect Journalists, told Forbidden Stories. “This is a very, very important problem that everyone needs to take seriously, not only in context of where journalists are working in a hostile environment for journalism, but in the US and Western Europe and other places.”

Countries where journalists were selected as targets FORBIDDEN STORIES

NSO group, in a written response to Forbidden Stories and its media partners, wrote that the consortium’s reporting was based on “wrong assumptions” and “uncorroborated theories” and reiterated that the company was on a “life-saving mission.”

“NSO Group firmly denies false claims made in your report which many of them are uncorroborated theories that raise serious doubts about the reliability of your sources, as well as the basis of your story,” the company wrote. “Your sources have supplied you with information that has no factual basis, as evidenced by the lack of supporting documentation for many of the claims.”

“The alleged amount of ‘leaked data of more than 50,000 phone numbers,’ cannot be a list of numbers targeted by governments using Pegasus, based on this exaggerated number,” NSO Group added.

In a legal letter sent to Forbidden Stories and its media partners, NSO Group also wrote: “NSO does not have insight into the specific intelligence activities of its customers, but even a rudimentary, common sense understanding of intelligence leads to the clear conclusion that these types of systems are used mostly for purposes other than surveillance.”

As dangerous as a suspected terrorist

For Szabolcs Panyi, an investigative journalist at Direkt36 in Hungary, learning that his cell phone had been infected with Pegasus spyware was “devastating.”

“There are some people in this country who consider a regular journalist as dangerous as someone suspected of terrorism,” he told Forbidden Stories over an encrypted line of communication.

Panyi is in his mid-30s. He wears round frame glasses, and has short stubble. The award-winning journalist has reported on defense, foreign affairs and other sensitive subjects and has a rolodex of thousands of contacts across multiple countries, including the United States, where he spent a year on a Fulbright scholarship – making him an ideal target for intelligence services, who are known to be distrustful of US influence in Hungary.

Panyi was working on two major scoops during the time his phone was compromised in 2019. Forbidden Stories, in partnership with the Amnesty International’s Security Lab, was able to confirm successful infections of his phone over a 9-month period from April to December. These infections, Panyi said, often matched his official requests for comment and important meetings with sources.

Hungarian journalist Szabolcs Panyi ANDRAS PETHO (DIREKT36)

One of the digital intrusions occurred when he was meeting with a Hungarian photojournalist who had been serving as a fixer for a reporter from a US-based news outlet working on a story about the International Investment Bank, a Russia-backed bank that in 2019 was pushing to establish branches in Budapest.

Around that time, the photojournalist fixer was also selected as a target, according to the records accessed by Forbidden Stories.

“It’s real likely that those who are operating this system were interested in what these Hungarian and American journalists were going to write about this Russian bank,” Panyi said.

Like Panyi, many journalists who are the subject of digital threats and cyber surveillance are interesting to state intelligence agencies on account of their sources, according to Igor Ostrovskiy, a private investigator in New York City who previously spied on journalists including Ronan Farrow, Jodi Kantor and Wall Street Journal reporter Bradley Hope as a subcontractor for the Israeli company Black Cube and now trains journalists in information security.

“We all know that journalists have a ton of information passing through their hands so that could be why state security could be interested,” he said. “State security could be interested in who’s leaking inside the government, or inside of a business that’s vital to the government, and they might be looking for that source.”

Halfway around the world, the phone of Paranjoy Guha Thakurta, an Indian investigative journalist and author of a number of books about Indian business and politics, was hacked in 2018. Thakurta told Forbidden Stories that he often spoke with sources on the condition of anonymity, and said that at the time of his targeting he was working on an investigation into the finances of the late Drirubhai Ambani, formerly the richest man in India.

“They would know who our sources were,” Thakurta said. “The purpose of getting into my phone and looking at who are the people I’m speaking to would be to find out who are the individuals who have been providing information to me and my colleagues.”

Thakurta is one of at least 40 Indian journalists selected as targets of an NSO client that appears to be the Indian government, based on the consortium’s analysis of the leaked data.

The Indian government has never confirmed nor denied being a client of NSO Group. “The allegations regarding government surveillance on specific people has no concrete basis or truth associated with it whatsoever,” wrote a spokesperson for the Ministry of Electronics and Information Technology in a response to detailed questions sent by Forbidden Stories and its partners.

While previous reporting showed four journalists among the 121 Pegasus targets revealed in India in 2019, the records accessed by Forbidden Stories show that this surveillance may have been much more extensive. More than 2,000 Indian and Pakistani numbers were selected as targets between 2017 and 2019, among them Indian journalists from nearly every major media outlet, including The Hindu, Hindustan Times, the Indian Express, India Today, Tribune, and The Pioneer. Local journalists were also selected as targets, including Jaspal Singh Heran, the editor in chief of a Punjab-based outlet that publishes only in Punjabi.

The phones of two of the three cofounders of the independent online news outlet The Wire – Siddharth Varadarajan and MK Venu – were both infected by Pegasus, with Venu’s phone hacked as recently as July. A number of other journalists who work for or have contributed to the independent news outlet – including columnist Prem Shankar Jha, investigative reporter Rohini Singh, diplomatic editor Devirupa Mitra and contributor Swati Chaturvedi – were all selected as targets, according to the records accessed by Forbidden Stories and its partners, which include The Wire.

“It was alarming to see so many names of people linked to The Wire, but then there are lots of people not linked to the Wire,” Varadarajan, whose phone was compromised in 2018, said. “So this seems to be a general predisposition towards subjecting journalists to high level surveillance on the part of the government.”

Many of the journalists who spoke with Forbidden Stories and its partner news organizations expressed dismay at having learned that despite the precautions they had taken to secure their devices – such as using encrypted messaging services and updating their phones regularly – their private information was still not secure.

“We’ve been recommending each other this tool or that tool, how to keep [our phones] more and more secure from the eyes of the government,” Ismayilova said. “And yesterday I realized that there is no way. Unless you lock yourself in [an] iron tent, there is no way that they will not interfere into your communications.”

Panyi worried that the public knowledge of his targeting could dissuade sources from getting in contact with him in the future.

“It’s every journalist who has been targeted’s concern that once it’s revealed that you were surveilled and even our confidential messages could have been compromised, who the hell is going to talk to us in the future?” he asked. “Everyone will think that we’re toxic, that we’re a liability.”

“Reading over your shoulder”: How Pegasus is used to spy on journalists in zero clicks

Amnesty International Security Lab’s forensics analyses of cell phones targeted with Pegasus as part of the Pegasus Project are consistent with past analyses of journalists targeted through NSO’s spyware, including the dozens of journalists allegedly hacked in the UAE and Saudi Arabia and identified by Citizen Lab in December of last year.

“There are a bunch of different pieces, essentially, and they all fit together very well,” Claudio Guarnieri, director of Amnesty International’s Security Lab, said. “There’s no doubt in my mind that what we’re looking at is Pegasus because the characteristics are very distinct and all of the traces that we see confirm each other.”

In all, the Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ) had previously documented 38 cases of spyware – developed by software companies in four countries – used against journalists in nine countries since 2011.

Eva Galperin, the director of cybersecurity at the Electronic Frontier Foundation (EFF), was one of the first security researchers to identify and document cyber attacks against journalists and human rights defenders in Mexico, Vietnam and elsewhere in the early 2010s.

At the time, in the early 2010s, most malware attacks were less sophisticated than they are today, she explained.

“Back in 2011, you would receive an email and the email would go to your computer and the malware would be designed to install itself on your computer,” she said.

It wasn’t until around 2014 that a “mobile-first” approach to spying on journalists gained popularity, as smartphones became more ubiquitous, she said. Clients of companies like NSO, Hacking Team and FinFisher used “social engineering” to send specifically-crafted messages to targets, often baiting them with information about potential scoops or targeted information about members of their families. Targets would have to click a link in order for the malware to be installed onto their phones.

Journalists are obvious targets for intelligence agencies, Ostrovskiy said, because they are always seeking new sources of information – opening themselves up to phishing attempts – and because many often don’t follow “industry best practices on digital security.”

Some of the first Pegasus infections of journalists were identified in Mexico in 2015 and 2016.

In January 2016, Carmen Aristegui, an investigative journalist in Mexico and the founder of Aristegui Noticias, began to receive messages with suspicious links after she published an investigation into property owned by former Mexican President Enrique Pena Nieto.

Aristegui received more than 20 text messages containing malicious Pegasus links, digital rights group Citizen Lab would later reveal in the 2017 Gobierno Espia (“Government Spying”) report. According to the report, the phones of a number of her colleagues and family members were also targeted with text messages containing malicious links during that same time period, including those of colleagues Sebastian Barragan and Rafael Cabrera and her son Emilio Aristegui – just 16-years-old at the time.

Forbidden Stories and its partners were able to identify for the first time three other people close to Aristegui who were selected as targets for surveillance in 2016: her sister Teresa Aristegui, her CNN producer Karina Maciel and her former assistant Sandra Nogales.

“It was a huge shock to see others close to me in the list,” Aristegui, who was part of the Pegasus Project, said. “I have six siblings, but at least one of them, my sister, was entered into the system. My assistant Sandra Nogales, who knew everything about me – who had access to my schedule, all of my contacts, my day-to-day, my hour-to-hour – was also entered into the system.”

Mexican journalist Carmen Aristegui PBS/FORBIDDEN FILMS

Since those early days, the installation of Pegasus spyware on smartphones has become more subtle, Guarnieri said. Instead of the target having to click on a link to install the spyware, so-called “zero-click” exploits allow the client to take control of the phone without any engagement on the part of the target.

“The complexity of performing these attacks has increased exponentially,” he said.

Once successfully installed on the phone, Pegasus spyware gives NSO clients complete device access and thereby the ability to bypass even encrypted messaging apps like Signal, WhatsApp and Telegram. Pegasus can be activated at will until the device is shut off. As soon as it’s powered back on, the phone can be reinfected.

“If someone is reading over your shoulder, it doesn’t matter what kind of encryption was used,” said Bruce Schneier, a cryptologist and a fellow at Harvard’s Berkman Klein Center for Internet and Society.

According to Guarnieri, Pegasus operators are able to remotely record audio and video, extract data from messaging apps, use the GPS for location tracking, and recover passwords and authentication keys, among other things. Spying governments have moved in recent years toward a more “hit and run” strategy to avoid detection, Galperin said: infecting phones, exfiltrating the data and quickly exiting the device.

These types of digital technologies go hand-in-hand with physical surveillance, according to Ostrovskiy.

“Digital intrusions are extremely valuable,” he said. “If we could, for instance, have known your calendar, if we could have known that you’re going to have a certain meeting or we could take a look at your email, your notes to whatever the materials that most of us have on our phones, we’d have a huge leg up in being more successful in whatever goal we’re trying to achieve.”

A new spyware marketplace

Surveillance of journalists is not new, security experts say. What has changed is the market for spyware.

Whereas in the past governments developed spyware tools in-house, private spyware companies like NSO Group, FinFisher and Hacking Team saw an opening for selling their products to governments who didn’t previously have the technical expertise to develop their own signals intelligence programs, according to Galperin. This created a sort of “wild west” of spying on journalists and activists, she said.

In its 2018 “Hide and Seek” report, digital rights organization Citizen Lab identified operators of NSO’s Pegasus in a number of countries with records of arbitrarily detaining journalists and human rights defenders, including Saudi Arabia, Morocco and Bahrain. Put together, NSO clients in these countries have selected tens of thousands of phone numbers, based on the consortium’s analysis of the leaked data.

Some reporters, like Moroccan freelance investigative journalist Omar Radi, whose cyber intrusion Forbidden Stories reported on in 2020, or Indian journalist and human rights defender Anand Teltumbde, were imprisoned after their phone infections were documented by advocacy groups and media outlets.

Spyware companies have faced relatively few legal or financial consequences for the use of their spyware against journalists and human rights defenders – although recent legal cases have begun to put pressure on these providers. In June 2021, French spyware company Amesys was charged with “complicity in acts of torture” for selling its spyware to Libya between 2007 and 2011. According to plaintiffs in that case, information gleaned through digital surveillance was used to identify and hunt down opponents of deposed dictator Muammar Gaddafi, who were later tortured in prison.

“If you are doing good journalism, you are speaking truth to power and you are pissing off people with power,” Galperin said. “The people who were doing journalism that was telling stories about corruption were often targeted. People who were doing activism that was again, protesting corruption, protesting authoritarianism, those were often the people who were on the front lines of being spied on.”

NSO Group maintains that its technology is used exclusively by intelligence agencies to track criminals and terrorists. According to NSO Group’s Transparency and Responsibility report, released in June 2021, the company has 60 clients in 40 countries around the world.

“[Pegasus] is not a mass surveillance technology, and only collects data from the mobile devices of specific individuals, suspected to be involved in serious crime and terror,” NSO Group wrote in the report.

Although the company also says that it has a list of 55 countries that it will not sell to on account of their human rights records, those countries are not listed in the report. According to the report, NSO Group has revoked access to five clients since 2016 after investigations into misuse and terminated contracts with five others that did not meet human rights standards.

“NSO Group will continue to investigate all credible claims of misuse and take appropriate action based on the results of these investigations,” NSO Group wrote in its statement to Forbidden Stories and its media partners. “This includes shutting down of a customer’s system, something NSO has proven it’s (sic) ability and willingness to do, due to confirmed misuse, done it multiple times in the past, and will not hesitate to do again if a situation warrants.”

Yet the leaked data show that many other authoritarian governments known to repress freedom of speech remain clients.

As part of the Pegasus Project, Forbidden Stories has been able to document the use of Pegasus for the first time in Azerbaijan. More than 40 Azerbaijani journalists were selected as targets, including reporters from Azadliq.info and Mehdar TV, two of the only remaining independent media outlets in the country.

In Azerbaijan, most independent news outlets are blocked and family members of journalists have routinely been harassed by the authorities. Under President Ilham Aliyev, whose family has ruled Azerbaijan for decades, the space for critical voices – according to Human Rights Watch – has been “virtually extinguished.”

Freelance journalist Sevinc Vaqifqizi’s phone was compromised between 2019 and 2021, according to an analysis conducted by Amnesty International’s Security Lab, in partnership with Forbidden Stories. As a freelance reporter for Mehdar TV, Vaqifqizi had already received a number of threats, and in February 2020 was badly beaten while covering a protest.

The reporter, in her early 30s with shoulder-length black hair, told journalists from the Forbidden Stories consortium that she already assumed the government had access to her private information.

“I said always to my friends that they can listen to us,” she said. “I’m worried about my sources who trust us and write us on WhatsApp. If they face some problems, that’s not good for us.”

Although she’s currently in Germany on a three-month fellowship, she did not feel safe from the authorities. As Amnesty International and others have documented, Azerbaijani activists have been physically and digitally targeted even after leaving the country.

“If you have a phone, they can probably continue [targeting you] in Germany,” she said.

Out of sight, not out of reach

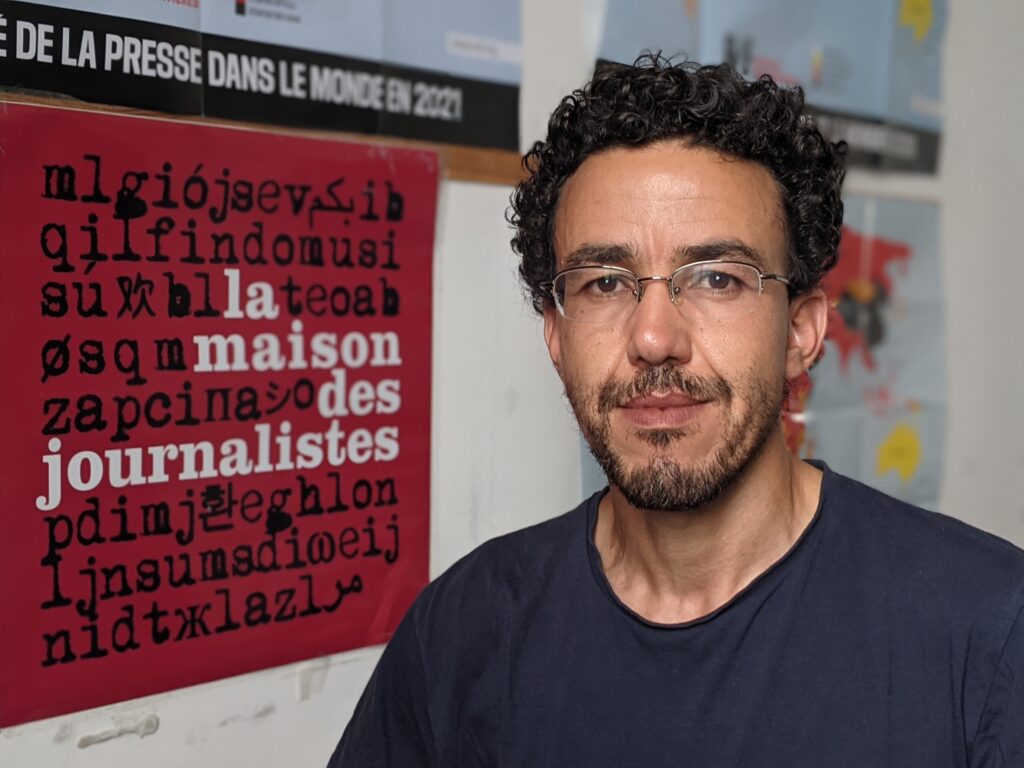

The walls of Hicham Mansouri’s office at the Maison des Journalistes (House of Journalists) in Paris are covered with posters from Reporters Without Borders and other press freedom advocacy organizations. The journalist used to lived in the building, which doubles as an exposition space and a residence for refugee journalists. He has since moved out, but still shares a small office on the ground floor where he goes to work three times per week.

Before speaking with Forbidden Stories, Mansouri turned off his borrowed phone and buried it deep in his backpack. According to a forensic analysis by Amnesty International’s Security Lab, Mansouri’s previous iPhone had been infected with Pegasus more than 20 times during a three-month period from February to April 2021.

Moroccan journalist Hicham Mansouri FORBIDDEN STORIES

Mansouri, a freelance investigative journalist and cofounder of the Moroccan Association of Investigative Journalists (AMJI, by its French initials) who is currently working on a book about the illegal drug trade in Moroccan prisons, fled Morocco in 2016 after numerous legal and physical threats against him.

In 2014, he was beaten by two unknown assailants after leaving a meeting with human rights defenders, including historian Maati Monjib, who was later targeted with Pegasus. A year later, armed intelligence agents raided his home at 9 a.m., finding him and a female friend in his bedroom together. They stripped him naked and arrested him for “adultery,” which is a crime in Morocco. He spent 10 months in a Casablanca prison, in a cell reserved for the most serious criminals that inmates had nicknamed “La Poubelle,” or “The Trash Bin.” The day after he was released from prison, Mansouri left Morocco for France, where he applied for and was granted asylum.

Five years later, Mansouri found out he was still a target of the Moroccan government.

“Every authoritarian regime sees danger everywhere,” Mansouri told Forbidden Stories. “We don’t see ourselves as dangerous because we do things that we consider to be legitimate, that we know are in our rights, but to them they’re dangerous.”

“They’re afraid of the sparks, because they know they’re flammable,” he added.

At least 35 journalists in four countries were selected as targets by an NSO client that appears to be the Moroccan government, based on the consortium’s analysis of the leaked data. Many of the Moroccan journalists selected as targets have been at some point arrested, defamed or targeted in some way by intelligence services. Others who were selected as targets – including most notably newspaper editors Taoufik Bouachrine and Soulaimane Raissouni – are currently in prison on charges that human rights defense organizations contend were instrumentalized in an effort to shut down independent journalism in Morocco.

In a statement shared with Forbidden Stories and its partners, a Moroccan embassy representive wrote that it did not “understand the context” of the questions sent by the consortium and was “waiting for material proof” of “any relationship between Morocco and the stated Israeli company.”

Bouachrine, the editor of Akhbar al-Youm, was arrested in February 2018 on charges of human trafficking, sexual assault, rape, prostitution, and harassment. Of 14 women who allegedly accused Bouachrine, 10 showed up to court and five declared that Bouachrine was innocent, according to CPJ. The publisher had previously penned op-eds critical of the Moroccan regime, accusing various high level government officials of corruption. He was sentenced to 15 years in prison, and spent more than a year in solitary confinement.

Forbidden Stories and its partners have been able to confirm that the numbers of at least two women involved in the case were selected as targets of Pegasus.

Bouachrine’s successor, Soulaimane Raissouni, was also arrested on sexual assault charges in May 2020, and was sentenced to five years in prison in July 2021. Raissouni was accused of assault by an LGBTQ activist, Adil Ait Ouchraa, who told CPJ that he hadn’t previously felt comfortable filing a public claim because of his sexual identity.

Journalists and press freedom advocates told CPJ they believed the claim had been filed as retaliation against Raissouni’s critical reporting. In 2021, still awaiting trial, Raissouni began a hunger strike that as of this writing, had lasted more than 100 days. His family members said that after 76 days he was in critical condition.

“The point [of surveillance] is presumably to track the private lives of individuals in order to find a hook on which they can hang any big trial,” said Ahmed Benchemsi, a former journalist and founder of the independent media organizations TelQuel and Nichane who now leads communications for the MENA region at Human Rights Watch.

While in the past Moroccan journalists were routinely hit with legal attacks for things they wrote – such as defamation or disrespecting the king – the new tactic was to accuse them of more serious crimes such as espionnage and later rape and sexual assault, he said. Surveillance emerged as a key tool in gleaning personal information that could be used to those ends.

“There’s often a sliver of truth to a large mass of slander, but that sliver of truth is usually something personal and confidential that can only come from surveillance,” he said.

Foreign journalists who have covered the plight of Moroccan journalists have also been selected as targets and in some cases their phones were successfully infected.

The phone of Edwy Plenel, the director and one of the cofounders of Mediapart, a French investigative journalism outlet, was compromised in the summer of 2019, according to an analysis by Amnesty International’s Security Lab that was peer-reviewed by the digital rights organization Citizen Lab.

In June of that year, Plenel had attended a two-day conference in Essaouira, Morocco, at the request of a journalist partner of Mediapart – Ali Amar, the founder of the Moroccan investigative magazine LeDesk – whose phone number also appears in the records accessed by Forbidden Stories. At the event, Plenel gave a number of interviews in which he spoke about human rights violations committed by the Moroccan state. Upon his return to Paris, suspicious processes began appearing on his device.

“We worked with Ali Amar; we published some investigations together and I knew Ali Amar, a bit like I know many of the journalists fighting for a free press in Morocco,” Plenel said in an interview with Forbidden Stories. “So when I learned about my surveillance, all of this made sense.”

Director of Mediapart Edwy Plenel PLACE AU PEUPLE / LICENCE CC BY-SA 2.0

Plenel said that the targeting of his phone and that of another Mediapart journalist, Lenaig Bredoux, with Pegasus was most likely a “Trojan Horse aimed at our Moroccan colleagues.”

Like Mansouri, many Moroccan journalists have either fled the country or stopped doing journalism altogether. Raissouni and Bouachrine’s newspaper, Akhbar al-Yaoum, burdened by their consecutive arrests and financial pressure, stopped publishing in March 2021.

“There was space for free speech in Morocco about 10 or 15 years ago,” Benchemsi said. “There is no more. It’s over. Surviving today means internalizing a high level of self-censorship, unless you support the authorities of course.”

A deadly weapon?

In NSO Group’s 2021 transparency report, one phrase appears three times: “save lives.” “Our goal,” the company writes at one point, “is to help states protect their citizens and save lives.” Yet the troubling use of NSO spyware against journalists and their family members, as identified in the Pegasus Project and in previous reports by digital rights NGOs, casts doubts on this narrative.

On October 2, 2018, around 1 pm, Washington Post columnist Jamal Khashoggi walked into the Saudi consulate in Turkey and never came back out. The brazen assassination of the dissident journalist initiated a wave of global responses, with world leaders, human rights groups and concerned citizens calling for an in-depth investigation into his murder – and the potential implication of NSO Group’s spyware in it.

Two weeks after his murder, digital rights organization Citizen Lab reported that a close friend of Khashoggi, Omar Abdulaziz, had been targeted with NSO’s Pegasus in the months before Khashoggi’s murder.

NSO, for its part, has repeatedly said that it has access to a “kill switch” and that it has revoked access to clients when human rights are not respected. The company has categorically denied any involvement in Khashoggi’s murder.

But new revelations from Forbidden Stories and its partners have found that Pegasus spyware was successfully installed on the phone of Khashoggi’s fiancée Hatice Cengiz just four days after the murder. The phone of Khashoggi’s son, Abdullah, was selected as a target of an NSO client that appears to be the UAE government, based on the consortium’s analysis of the leaked data, several weeks after the murder. Close friends, colleagues and family members of the murdered journalist were all selected as targets by NSO clients that appear to be the governments of Saudi Arabia and the UAE, according to the Pegasus Project revelations released today.

Hatice Cengiz, Jamal Khashoggi’s fiancée PBS/FORBIDDEN FILMS

“As NSO has previously stated, our technology was not associated in any way with the heinous murder of Jamal Khashoggi,” NSO Group wrote in its letter to Forbidden Stories. “We can confirm that our technology was not used to listen, monitor, track or collect information regarding him or his family members mentioned in your inquiry.”

Khashoggi’s death, and the spyware lingering on the margins of it, security experts say, was not necessarily a unique case.

“[Khashoggi is] certainly not the first journalist to have been killed by an angry government. And he’s not the first journalist to have been killed by an angry government for his journalism with some element of malware and surveillance involved,” Galperin, at EFF, said. “These are things that very frequently go together.”

On March 2, 2017, local Mexican journalist Cecilio Pineda took out his phone and recorded his final broadcast. In it, the reporter from the city of Altamirano, who ran a Facebook with more than 50,000 followers, spoke about alleged collusion between state and local police and the leader of a drug cartel.

Two hours later, he was dead – shot at least six times by two men on a motorcycle as he lay in a hammock outside of a car wash.

When Pineda was assassinated in 2017, at the age of 38, the world blinked and moved on. His death was seen as just another reporter killed in Mexico – the deadliest non-conflict zone in the world to be a journalist. But Pineda’s death may have been more than a drive-by job by a local cartel, according to the records accessed by Forbidden Stories and its partners.

Just a few weeks before he was killed, Pineda’s work cell phone was selected as a target of an NSO client in Mexico.

Forbidden Stories has been able to confirm that not just Pineda, but also the state prosecutor who investigated the case, Xavier Olea Pelaez, were selected as targets of Pegasus in the weeks and months before his murder. Forbidden Stories was unable to analyze Pineda’s phone because it disappeared immediately after his death. Pelaez did not keep his phone from the time, so it was not possible to confirm an infection by Pegasus.

Pineda’s reporting, however, gives traces as to why Pineda’s work could have troubled Mexican authorities who may have had access to this technology. At the time of his selection, Pineda was investigating links between the local crime boss, known as El Tequilero, and the governor of the state of Guerrero, Hector Astudillo. Friends and family who spoke with Forbidden Stories and its partners said that Pineda had received threats and had asked to be placed in a federal mechanism for the protection of journalists.

“Cecilio received many serious threats but he would play them down,” Israel Flores, a friend of Pineda’s, said in a recent interview. “He’d always say ‘nothing will happen.’”

As Pineda continued to report on the nexus of local politicians and drug traffickers, the threats came ever closer to him. A few days before his death, men in a white car took photos of his home, his mother said.

The day he was killed, he stopped by his mother’s house before meeting a friend at a political rally. That was the last time she saw him.

“He told me ‘the bad guys aren’t going to kill me, they know me, they’re my friends. If they kill me it will be the government,” her mother said in an interview.

Pineda’s wife, Marisol Toledo, told a member of the Forbidden Stories consortium that the day after Pineda’s death she received a call from a government employee who told her he was investigating the murder. He never followed up.

“We don’t know what happened in the investigation,” Toledo said. “We don’t want trouble. People with power can do what they want, to who they want.”

Pineda’s phone was also never found – as it had disappeared from the crime scene by the time the authorities had arrived. But when told about the possible role of spyware in tracking Pineda’s movements, Toledo was not surprised.

“If they succeeded, they would have known where he was at all times,” she said.

Additional reporting by Nina Lakhani (The Guardian) in Mexico, Kristiana Ludwig (Suddeutsche Zeitung) in Germany, Miranda Patrucic (OCCRP) in Turkey and Sandhya Ravishankar (The Lede) in India.